Leith Walk botanical cottage, demolished and risen again

Best of

The campaign to bring a small eighteenth-century building in Edinburgh back to its former glory

Before I left Edinburgh six months ago I lived in Broughton, just off the top of Leith Walk. It was originally a village, one of the many you’ll find chipped away and consumed by the city as it grows ever larger.

As with all Edinburgh the area has plenty of history for those who know where to look. Iceland’s national anthem was written in a house in London Street during the decades its people fought for a republic. Within five minutes’ walk from my house you could wander along East London Street, up Annandale Street, turn onto Leith Walk, and — if you knew where to look — you could see the first house built for the keeper of the city’s botanical garden.

Constructed in the eighteenth century before the garden moved to Inverleith, the house was in a terrible state. The ground floor was mostly underground and a modern door had been rudely transplanted onto the first floor. The windows were boarded up. The mortar was decaying, the stone crumbling. Part of the left side had been demolished to make way for a nineteenth century tenement. It was a shell, empty and forgotten.

I have no idea how I knew this broken cottage was the first gardener’s house. There was no plaque, no signposts, nothing. I must have read it somewhere, in some anonymous book or leaflet. It felt like my own secret, something only I knew.

During the last few weeks of my time in the city, it was demolished.

I couldn’t believe it. That little building, pushed around by the bullying tenements of Leith Walk, was being destroyed. For 250 years it had struggled to survive; it had been left alone when the garden moved, no longer needed. Finally, after stints as slum housing and a car rental office, it had given up the fight and was gone. I was heartbroken. As I left the city, so did the gardener’s house.

The cottage as it looked in June 2008, shortly before it was demolished. The original ground floor was by this point underground and a first-floor window had been converted into a door. Courtesy Google Maps

There was something peculiar — or rather, particular — about the way the house was demolished. I would have expected the demolition company to knock it down as quickly and as cheaply as possible. But first the slate roof was removed and then the stones were taken down. That removal, almost a stripping of the building layer by layer, niggled at me. Why demolish it like that? Why spend that time and effort destroying something?

Six months later I had the answer. The house still existed.

I say existed; the house was no longer an arrangement, an entity in itself. It was pieces; pieces on palettes, in storage. Someone had taken care not to forget it: each part, each timber, each slate, each stone, was numbered. The house was no longer a building, but a puzzle.

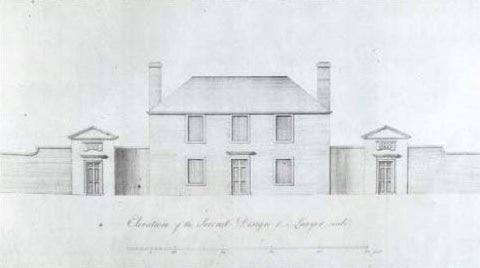

As he explained in a lecture to the Architectural Heritage Society of Scotland, James Simpson, a partner at Simpson & Brown Architects, kept the house. It started with a drawing, a plan of a cottage. The cottage was the gardener’s house on Leith Walk, although Simpson didn’t know that at the time. But he thought the building had the distinct look of John Adam, one of the three Adam brothers that had such an effect on Edinburgh’s architecture.

James Craig’s drawing of the Leith Walk botanical cottage.

It was the start of a love affair for Simpson. He spent time researching the drawing. He discovered the artist was James Craig, no other than the man that drew up the plans for the New Town. Craig worked in the office of John Adam and had links with Dr John Hope, the man who was developing the land around what we now know as Leith Walk.

In the 1760s Hope asked the prime minister, Lord Bute, for a new botanical garden. He got one. The architect of the garden was William Robertson — of whom we know nothing more than his name — while John Adam was asked to design the gardener’s house. Craig made the drawing of Adam’s design and, Simpson discovered, was later given the commission to lay out Leith Walk. (Craig raised the level of the street by eight foot, placing the ground floor of Adam’s house underground, no doubt accelerating the garden’s move to Inverleith.)

When Simpson heard the house was to be demolished he decided to save it. A committee was formed, and they applied to the Heritage Lottery Fund for a grant. To their great surprise, they got it.

Next they went to the land’s developer, Cobalt, and asked if they could perform an archaeological survey. This would take time and involve digging up the land so they weren’t confident they’d get what they wanted. But again, to the committee’s surprise, Cobalt not only agreed but also offered to pay. The archaeological dig found, below ground level, the screen walls that extended out from the house.

Then they started to take the house down. Piece by numbered piece, the house was lovingly interred in bags. They removed the first-floor ceiling only to find it wasn’t a two-story house, but a three-story house. The attic had been the first gardener’s lecture theatre. An external staircase was added in 1802 and once they took that down they realised there had been a viewing platform in the lecture theatre, extending out to look across the garden.

Pushing their luck, the committee spoke to the current head of the botanical garden, the Regius Keeper: might the cottage be found a place in the garden? Yes, it could. And so started plans to place the cottage in a line with Inverleith House, with a long path stretching down the hill between the two. In the middle of the path would be the re-sited monument to Linnaeus, designed by James Craig for Dr John Hope, the Leith Walk garden’s first gardener and the cottage’s first occupant. The plaque commemorating John Hope’s work that now sits hidden in a corner of Inverleith would be moved to the screen walls, to its original place as shown in James Craig’s drawing.

It’s only a plan, and there’s much to do — not least to find the money to rebuild the house. Simpson wants trainee masons from Telford College to rebuild the house using the original eighteenth-century methods. He wants the BBC to film it.

After spending six months thinking the Leith Walk gardener’s cottage was lost I’m overjoyed to know it has a future ahead of it as an integral part of the garden it once served. I’m excited to see the community that has grown up around it, and I’m glad someone as far-sighted as Simpson is in charge.

Update, 11th January 2021

A decade later and the cottage is rebuilt (as of 2016) and it looks beautiful in the grounds of the Royal Botanical Gardens. If you want to know more about the history of the cottage and its rebuilding you should read Kennedy Dold’s 2019 undergraduate dissertation, ‘The oldest and youngest building’: the botanic cottage at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh in context. Historic Environment Scotland has photos of the cottage in disrepair in 2008 before it moved from Haddington Place on Leith Walk. Simpson & Brown have a short review of the project.